Throwing away the law books

Oct. 26th, 2018 11:01 amI loved my husband, heaven knows, but he was a hoarder.

By the time he was eighteen, Rob had moved eighteen times. My theory is that this trained him to understand that his home wasn't a place, it was his things. They were what was permanent. Therefore, he had to keep them permanently.

And he did.

When Rob was going to the University of Minnesota law school, he worked at the law library. One day, he discovered that the law library was discarding a ton of huge, heavy law books. Rob volunteered to take them, and the library said sure, they're yours. For free.

When Rob set up his law office, he proudly shelved them in floor-to-ceiling bookshelves that covered all the walls of his entire office. To him, they looked cool. They meant that he had made it. He was an attorney.

When he had to shut his office down, he decided to put them into storage. Remember, he is not allowed to get rid of anything. I am ashamed to tell you how many thousands of dollars he paid for storage--he had that storage unit for over a decade. The waste of money aggravated me so much--how much of that money could have gone for our daughters' college tuition instead? Finally, when he lost his job and the walls were closing in, I insisted that he couldn't rent storage anymore.

So the law books and all the contents of his law office came to live in our garage. Rob parked his car out on the street instead of keeping it in a garage as any sane Minnesotan would. And he had to clear the snow off of it and move it from one side of the street to another during snow emergencies. He did this uncomplainingly for year after year.

For years I nagged him to deal with all debris from the law practice. But he never did. There was another TV show to watch, another thing to do with the girls. He told me the books were valuable. "Fine," I said. "We can use the money. Let's sell them." But he could never figure out who might take them. He talked about advertising on Craigslist (do people shop for law libraries on Craigslist?) but never did. It was obviously crazy to advertise online for a national buyer: the books were so big and so heavy that the shipping costs would kill us. Once, when we were holding a garage sale, he put a sign on the towering pile of boxes of books: "Law Library Wall O'Books. $3,000.00."

As if anyone shopping at a garage sale might think, "Wow, a whole law library! I just happen to have $3,000.00 in my pocket, and I should snap that right up. What a bargain!

Then he got sick.

As he became weaker, he fretted about his possessions. And seeing how it was stressing him out, I made a difficult promise: I wouldn't throw anything of his away without his permission.

Now he is gone. I haven't started dealing with the law office files (an attorney I know has promised to help with that, but his help has been delayed because his own father has died and he's still dealing with that estate).

But I have started dealing with the law books.

I tried. I called the Minnesota Women's Prison Book Project, asking if they could use them as a donation. Perhaps women who are working on their appeals might consult them? No. Too big. Too heavy. No space to put them. And (this is obvious to anyone who has worked in the law the last quarter century, and it's why the law library was throwing them away in the first place) attorneys use Westlaw and Lexis now. They don't look up statutes in moldering law books.

I called a friend of mine who works at Thomson Reuters, the successor to Westlaw, the original publisher to ask what value the books might have. "None," was his blunt answer. "Recycle them."

So I have been going out to the garage every couple of weeks and emptying one box at a time, ripping off the rotting leather covers and throwing the stripped books into the dumpster. It's painful. It's galling (I'm an author. I write books. Destroying them is an appalling thing to have to do.) And I can hear Rob screaming in the back of my mind, "Noooooooo! You can't do this to those books." (Which really means, "You can't do this to me!")

But Rob is gone.

The leatherbound books are large and crumbling. The oldest ones are from the end of the 19th century.

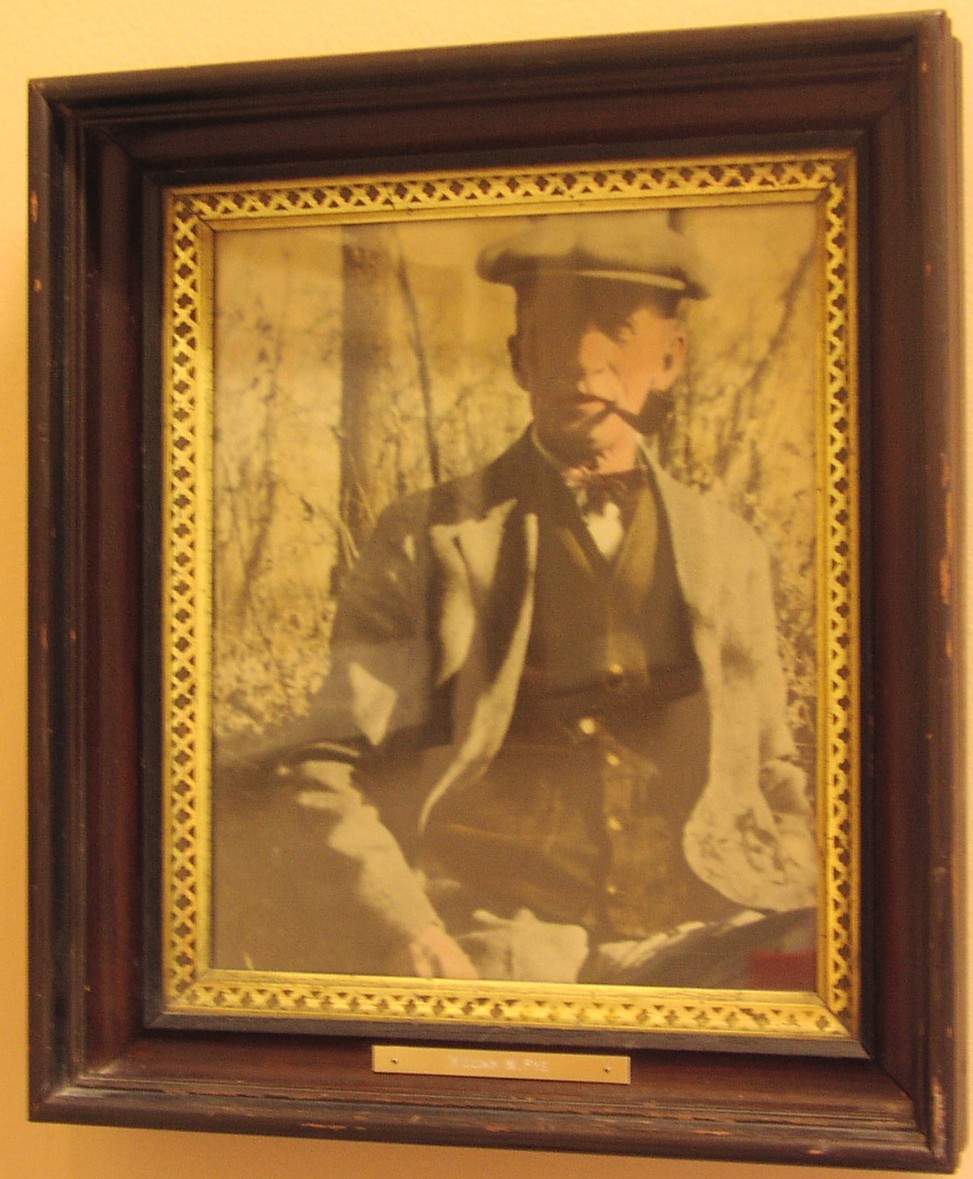

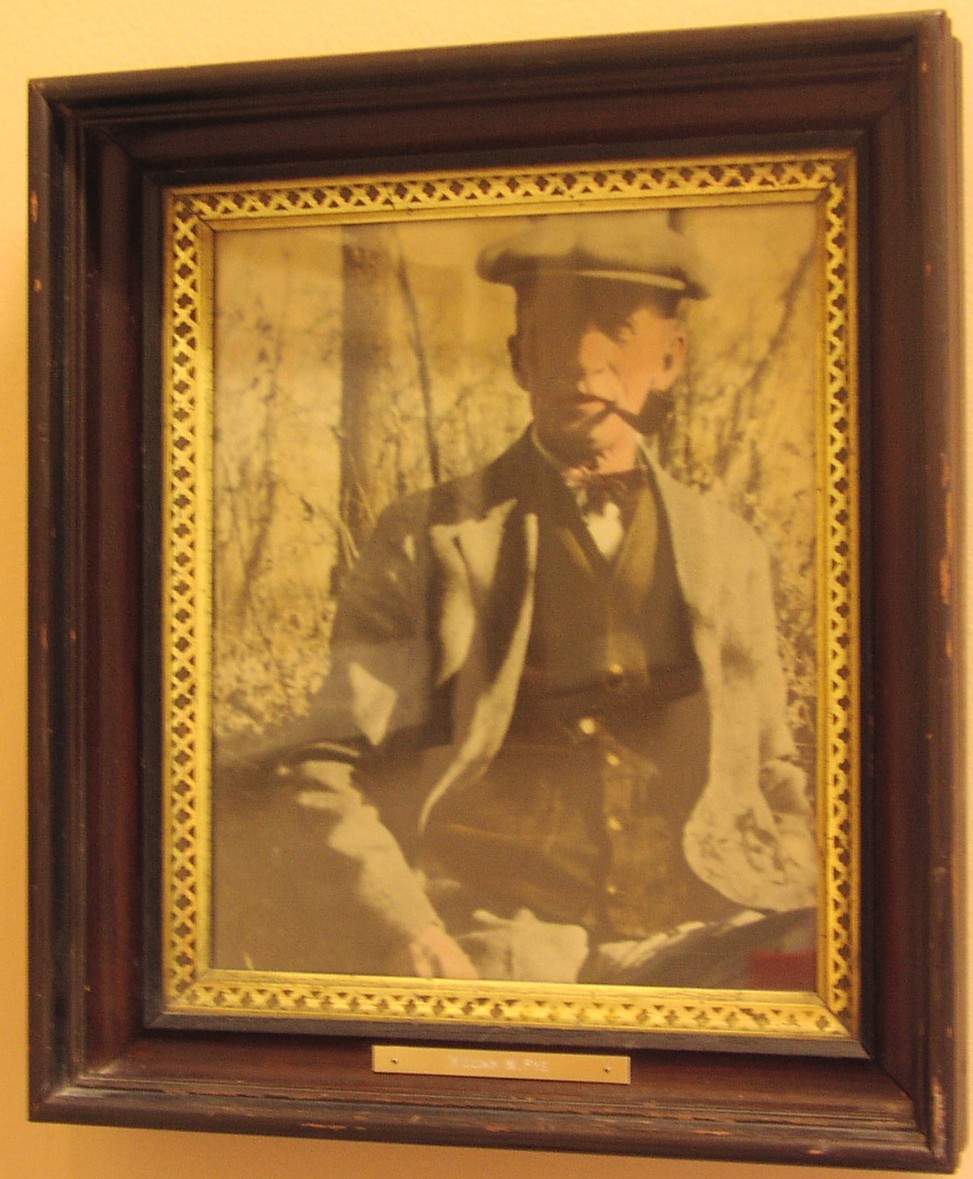

They are stamped inside a stamp for the U of MN library, and also with a name: "William W. Pye."

I did some online research and discovered he was an attorney and bank president who lived from 1870-1965 in Northfield, Minnesota.

(And now I'm feeling guilty again like I should have offered them to the Northfield library. They have a room there named after him). Presumably, after he died, they were donated to the U of MN law library. I wonder if his wife wanted them out of her house, too.

I threw away three boxes this morning, which was all I could bear to do at once.

I thought of Rob. I thought of William W. Pye. I went into the house and washed the skins flakes of cows that died 120 years ago off my hands. I managed not to cry.

This is so damned hard.

By the time he was eighteen, Rob had moved eighteen times. My theory is that this trained him to understand that his home wasn't a place, it was his things. They were what was permanent. Therefore, he had to keep them permanently.

And he did.

When Rob was going to the University of Minnesota law school, he worked at the law library. One day, he discovered that the law library was discarding a ton of huge, heavy law books. Rob volunteered to take them, and the library said sure, they're yours. For free.

When Rob set up his law office, he proudly shelved them in floor-to-ceiling bookshelves that covered all the walls of his entire office. To him, they looked cool. They meant that he had made it. He was an attorney.

When he had to shut his office down, he decided to put them into storage. Remember, he is not allowed to get rid of anything. I am ashamed to tell you how many thousands of dollars he paid for storage--he had that storage unit for over a decade. The waste of money aggravated me so much--how much of that money could have gone for our daughters' college tuition instead? Finally, when he lost his job and the walls were closing in, I insisted that he couldn't rent storage anymore.

So the law books and all the contents of his law office came to live in our garage. Rob parked his car out on the street instead of keeping it in a garage as any sane Minnesotan would. And he had to clear the snow off of it and move it from one side of the street to another during snow emergencies. He did this uncomplainingly for year after year.

For years I nagged him to deal with all debris from the law practice. But he never did. There was another TV show to watch, another thing to do with the girls. He told me the books were valuable. "Fine," I said. "We can use the money. Let's sell them." But he could never figure out who might take them. He talked about advertising on Craigslist (do people shop for law libraries on Craigslist?) but never did. It was obviously crazy to advertise online for a national buyer: the books were so big and so heavy that the shipping costs would kill us. Once, when we were holding a garage sale, he put a sign on the towering pile of boxes of books: "Law Library Wall O'Books. $3,000.00."

As if anyone shopping at a garage sale might think, "Wow, a whole law library! I just happen to have $3,000.00 in my pocket, and I should snap that right up. What a bargain!

Then he got sick.

As he became weaker, he fretted about his possessions. And seeing how it was stressing him out, I made a difficult promise: I wouldn't throw anything of his away without his permission.

Now he is gone. I haven't started dealing with the law office files (an attorney I know has promised to help with that, but his help has been delayed because his own father has died and he's still dealing with that estate).

But I have started dealing with the law books.

I tried. I called the Minnesota Women's Prison Book Project, asking if they could use them as a donation. Perhaps women who are working on their appeals might consult them? No. Too big. Too heavy. No space to put them. And (this is obvious to anyone who has worked in the law the last quarter century, and it's why the law library was throwing them away in the first place) attorneys use Westlaw and Lexis now. They don't look up statutes in moldering law books.

I called a friend of mine who works at Thomson Reuters, the successor to Westlaw, the original publisher to ask what value the books might have. "None," was his blunt answer. "Recycle them."

So I have been going out to the garage every couple of weeks and emptying one box at a time, ripping off the rotting leather covers and throwing the stripped books into the dumpster. It's painful. It's galling (I'm an author. I write books. Destroying them is an appalling thing to have to do.) And I can hear Rob screaming in the back of my mind, "Noooooooo! You can't do this to those books." (Which really means, "You can't do this to me!")

But Rob is gone.

The leatherbound books are large and crumbling. The oldest ones are from the end of the 19th century.

They are stamped inside a stamp for the U of MN library, and also with a name: "William W. Pye."

I did some online research and discovered he was an attorney and bank president who lived from 1870-1965 in Northfield, Minnesota.

(And now I'm feeling guilty again like I should have offered them to the Northfield library. They have a room there named after him). Presumably, after he died, they were donated to the U of MN law library. I wonder if his wife wanted them out of her house, too.

I threw away three boxes this morning, which was all I could bear to do at once.

I thought of Rob. I thought of William W. Pye. I went into the house and washed the skins flakes of cows that died 120 years ago off my hands. I managed not to cry.

This is so damned hard.